Cyanobacteria (Stanieria) in 252 Ma Old Microbialites in South ChinaUpdate time:06 20, 2016

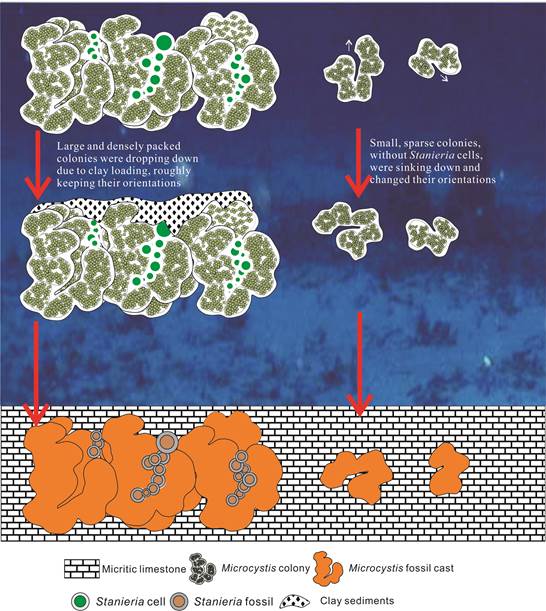

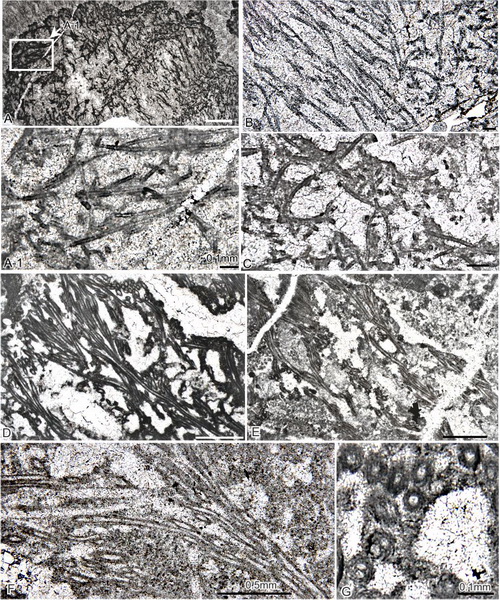

A recent study performed by Wu Yasheng from IGG revealed that mysterious tiny globular fossils found in Permian-Triassic boundary microbialites are actually calcified fossils of Stanieria, a genus of Chroococcophyceae cyanobacteria that exists in present-day shallow seas. The work, conducted by Chinese and foreign paleontologists, found that some unknown factors may have triggered the most severe biotic crisis in Earth’s history, which is marked by the sudden disappearance of more than 95% of marine and more than 75% of terrestrial species. After the catastrophe, thick successions of microbialites formed in the shallow seas in what is not modern day South China. The strange rocks are characterized by dendroid or reticulate appearance on outcrop. Earlier work in 2003 by the Japanese paleontologist Ezaki, together with Jian-Bo Liu from Peking University found tiny coccoid fossils in the microbialites. Following that, many other researchers encountered this kind of fossils. However, for more than 13 years, no one could find out what organisms the fossils really were and what role they played in the 252 Ma old shallow seas. Examination of thin sections of the rocks by Wu and his colleagues revealed that the mysterious coccoid fossils resemble modern Stanieria cells in all main aspects. Both are: (1) spherical in shape, (2) are 5 to 49 µm in size, (3) distributed in patches, and (4) reproduced via baeocytes (microspores). Thus, these coccoid fossils are interpreted as calcified fossils of ancient Stanieria cells. Modern Stanieria cells live on the shallow marine floor. Did the ancient Stanieria cells live in the same way? Wu and his colleagues found the coccoid fossils occur together only with densely packed Microcystis fossils, and are never singly present. In a recent study Wu and others revealed that the microbialites were mainly composed of fossils of Microcystis, a colonial cyanobacterial genus that commonly forms algal blooms in present-day rivers, lakes, and marine waters. Wu's team speculated that the ancient Stanieria cells attached themselves to Microcystis and their associated algal blooms (see the Figure). This study reveals a new lifestyle for this kind of organisms.

Illustration of Microcystis bloom and the hitch-hiking lifestyle of Stanieria cells in the Permian–Triassic transition seas. Contact:

|

Contact

WU Yasheng

Division: Petroleum Resources Goup: Fluid dynamics of petroliferous basins Phone: 86-10-82998342 E-mail: wys@mail.iggcas.ac.cn Reference

|

-

SIMSSecondary Ion Mass Spectrometer Laboratory

-

MC-ICPMSMultiple-collector ICPMS Laboratory

-

EM & TEMElectron Microprobe and Transmission Electron Microscope Laboratory

-

SISolid Isotope Laboratory

-

StIStable Isotope Laboratory

-

RMPARock-Mineral Preparation and Analysis

-

AAH40Ar/39Ar & (U-Th)/He Laboratory

-

EMLElectron Microscopy Laboratory

-

USCLUranium Series Chronology Laboratory

-

SASeismic Array Laboratory

-

SEELaboratory of Space Environment Exploration Laboratory

-

PGPaleomagnetism and Geochronology Laboratory

-

BioMNSFrance-China Bio-mineralization and Nano-structure Laboratory

Print

Print Close

Close