A collaborative research team from IGGCAS, Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Linyi University, the Administration Center of Shangshan Site, and experts from 13 institutions nationwide conducted an in-depth study on the origins of rice in the Shangshan cultural area of Zhejiang. Utilizing phytolith analysis and other methods, the team unveiled the continuous evolutionary history of rice from wild to domesticated over an astounding span of 100,000 years. This research provides new evidence for understanding the development of human society and the origins of agricultural civilization, confirming that China is the birthplace of rice (Oryza sativa). Additionally, it underscores the significance of the Shangshan culture in the origins of global agriculture. The research results were published online as a research article on May 24, 2024, in the internationally renowned academic journal, Science.

The origin of agriculture marks a crucial turning point in human society, transitioning from a hunter-gatherer economy to an agricultural production economy, thus initiating the dawn of human civilization. Rice, as the staple food for half of the world's population, has profoundly impacted the formation and development of Chinese civilization through its cultivation and domestication. Questions such as when humans began to explore wild rice and how the process from domesticating wild rice occurred have long been focal points for various disciplines.

Over the past century, the study of rice origins has been a contentious topic, with theories proposing origins in India, Southeast Asia, Assam, and Yunnan. It was not until the discovery of rice archaeological evidence at sites such as Hemudu, Shangshan, and other locations in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River since the 1970s that the international academic community began to recognize this region as a significant area origin for rice. However, finding long-preserved identifiers that can distinguish wild and domesticated rice in the Yangtze River basin since the last glacial maximum and uncovering the processes and mechanisms of human collection and domestication of wild rice remain key challenges for breakthroughs in this research.

In the latest study, the research team led by Dr. LU Houyuan at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, built on years of systematic research on phytoliths in modern wild and domesticated rice plants and soils. They clarified that the increase in the number of fish-scale facets on the bulliform phytoliths of rice correlates with enhanced domestication and agronomic traits. By establishing the threshold for distinguishing wild rice from domesticated rice based on the proportion of bulliform phytoliths with fish-scale facets, they set standards for identifying wild and domesticated rice.

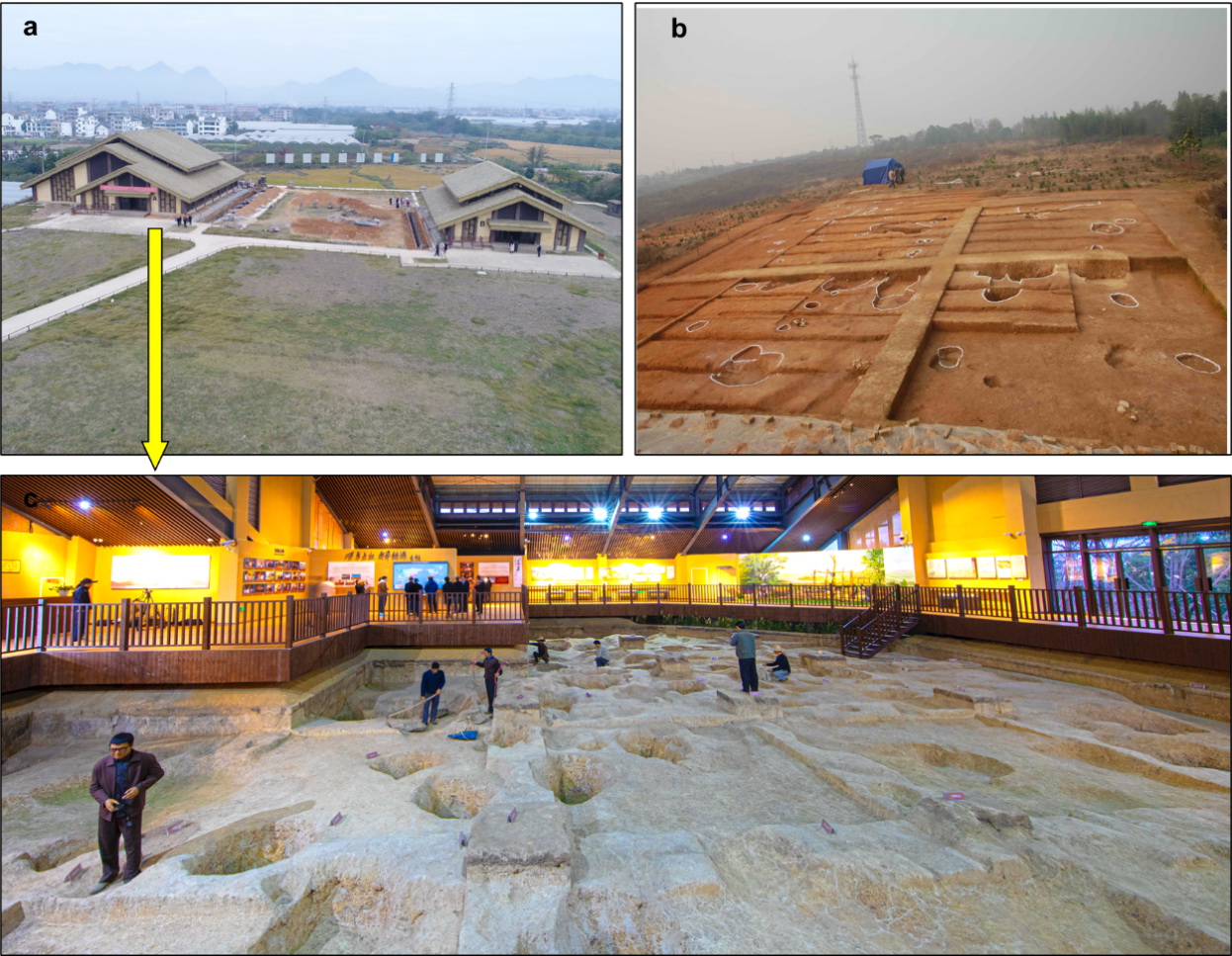

The researchers employed phytolith analysis, combined with pollen, charcoal, soil microstructure, grain size, magnetic susceptibility, geomorphological surveys, 14C probability density analysis of archaeological sites, and archaeological excavations, to conduct systematic studies on the archaeological stratigraphy and natural profiles of the Shangshan site in Pujiang County and the Hehuashan site in Longyou County, Zhejiang. Using Bayesian models of high-precision optically stimulated luminescence ages and phytolith 14C ages from these sites, they established a continuous chronological sequence dating back approximately 100,000 years. Systematic analysis of samples from these stratigraphic sequences revealed the continuous trajectory of rice from wild to domesticated within the stratigraphy of the Shangshan cultural site area and its relationship with human activities and climate change (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Topographic map showing the locations of the archaeological sites of (a and c) Shangshan and (b) Hehuashan. Images (a) and (c) are provided by Prof. ZHANG Jianping, and image (b) is provided by Prof. JIANG Leping.

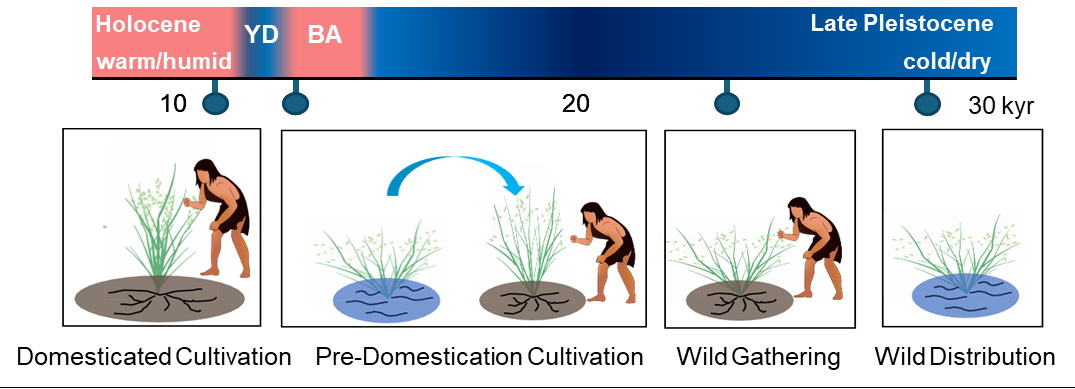

The research indicates that wild rice was already distributed in the lower Yangtze region approximately 100,000 years ago, providing conditions for subsequent rice use and domestication. Around 24,000 years ago, as the climate began to enter the Last Glacial Maximum, humans started collecting and using wild rice, indicating an adaptation to explore new food sources in response to cold climate changes. Around 13,000 years ago, humans began pre-domesticated cultivation of wild rice. About 11,000 years ago, the proportion of domesticated rice phytoliths rapidly increased, reaching domestication thresholds, thereby marking the origin of rice agriculture in East Asia. This study demonstrates that the origins of rice agriculture in East Asia and wheat agriculture in Southwest Asia were synchronous, representing a significant milestone in human development and greatly deepening our understanding of the global origins of agriculture.

The 100,000-year continuous evidence from wild rice distribution to eventual domestication at the Shangshan cultural site reveals the complex relationship between rice, climate, human activities, and cultural development, highlighting the prolonged domestication process of rice. The research has received high praise from peer reviewers, who consider this innovative discovery a major contribution to the study of human-rice co-evolution. This work significantly impacts our understanding of human societal development, the origins of agricultural civilization, and the importance of Shangshan culture (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Conceptual model from rice exploitation to domestication since 30 kyr BP in the Lower Yangtze River region. Images provided by Prof. ZHANG Jianping.

Dr. ZHANG Jianping of IGGCAS, is the first author of the study, with Dr. LU Houyuan as a co-first author. Dr. LU Houyuan, Dr. ZHANG Jianping, Dr. JIANG Leping from the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, and Professor YU Lupeng from Linyi University are co-corresponding authors. Experts and scholars from Peking University, Fujian Normal University, Shandong University, Yunnan Normal University, Hebei Normal University, the Administration Center of Shangshan Site, Pujiang Museum, Longyou Museum, and the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences participated in the collaborative research.

Phytolith: Phytolith is a microscopic silica body that forms in the cells and intercellular spaces of higher plants. They are created when plants absorb soluble silica through their roots, which is then transported to stems, leaves, fruits, and other parts, where it precipitates and solidifies into amorphous silica particles.

Cultivation: Cultivation refers to the human practice of managing plant growth without altering the plants' genetic traits.

Predomestication Cultivation: This is the process by which humans, intentionally or unintentionally, manage the growth of plants without changing their wild genetic traits.

Domestication: Domestication is the process by which humans alter the genetic traits of plants, making them more suited to cultivation in artificial environments.

Last Glacial Maximum (LGM): The Last Glacial Maximum occurred approximately 26,500 to 19,000 years ago. During this period, global temperatures were 5 to 10°C cooler than today, and sea levels were likely 120-135 meters lower than present levels.

Contact:

ZHANG Jianping

Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences

E-mail: jpzhang@mail.iggcas.ac.cn